In our previous post, we understood how the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) functions as a decentralized and patient-centric consent management architecture and how it has been deployed under the existing India Stack. We then uncovered how it attempts to solve the biggest problem in the digital healthcare ecosystem: interoperability, and the role that the DEPA has taken under the Health Stack. Before we discuss the solutions that it has provided to tackle the existing privacy concerns, under the ABDM ecosystem, let’s first understand the context of its application in health data. How will this consent mechanism impact the flow of health data under the ABDM? Why is health data so sensitive in the first place? Is health data posed with a unique set of challenges and risks, to which the DEPA would need to adapt?

Role of Consent in Health Information Exchange (HIE)

Before addressing this, it’s important to understand the role and significance of user consent specifically in the context of health data. Why is there a need for patient-centric data transfers? Does health data pose any risks that are more significant or nuanced, as compared to other forms of data? Why is health data even at such a great risk of disclosure, leaks, and misuse?

Personal data pertaining to an individual’s health plays an extremely unique role in the grand scheme of data management and information exchange. Primarily for five reasons:

- The Nature and Sensitivity of the Data

Health data exists at the intersection of five different elements of privacy [1] – Informational Privacy (Confidentiality, Anonymity, Secrecy and Data Security), Physical Privacy (Modesty and Bodily Integrity), Associational Privacy (Intimate sharing of details on death, illnesses, sexual activities, etc.), Proprietary Privacy (Self-ownership, control over Personal Identifiers, Genetic Data, etc.) and Decisional Privacy (Autonomy and choice in medical decision-making). This unique and complex intersectionality puts health data at greater risk, making it more susceptible to misuse. - The Lack of a Unified Regulatory Mechanism

At present, no unified structure, system, or platform for collecting, storing, handling, processing, and transfer of health data exists. The propositions under the Draft Health Data Management Policy, despite being transformative and privacy-centric, are still in the deliberation stage and far from any enforcement. Data (online or offline) existing in the health ecosystem is regulated and controlled by multiple industry-specific standards and guidelines, all functioning independently, with little interoperability between them. India is severely struggling from a lack of robust cyber security systems and practices, the consequences of which we are witnessing through repeated health data breaches across the public and private sectors. - The Enormous and Vast Economic Potential of Health Data

The healthcare sector is an extremely information-intensive industry. Health data breaches are an extremely common occurrence globally in the form of organized crime, with each data breach costing up to $10.93 million on average. [2] This proves that health data is an extremely valuable commodity, even compared to other forms of sensitive personal data, such as financial data, where each breach costs an average of $5.9 million. [3] This acts as a huge incentive for cybercriminals to target health data and records of Personal Health Information (PHI). In fact, hacking and cyber crimes are the leading causes of health data breaches, amounting to 79.8% of all incidents. [4] Health data can be used for innumerable things, such as for targeted scams & frauds and false insurance claims in order to gain access to prescriptions for further resale, targeted advertisements, and several other reasons. Attackers can even acquire intellectual property through such data sets, such as drug formulas, manufacturing processes, trade secrets, etc. - Medical Confidentiality

It is presumed that when a patient visits a healthcare professional for a consultation, they are impliedly consenting to provide medical information that may be shared for the purposes of receiving accurate and informed treatment. [5] However, patient data is held under the duty and responsibility of confidentiality to be exercised by the healthcare professional. The principles of confidentiality are even instilled in the Hippocratic Oath. Implied consent is a common industry practice in healthcare, but this does not equate to informed consent requirements under privacy mandates. [6] However, robust anonymization mandates that are enforceable and foresee the risks of de-anonymization or re-identification would be an ideal solution for this problem. - The Inherent Personal and Intimate Nature of Health Data

As highlighted above [7], health data carries several risks especially related to physical and associational privacy. It can often declare extremely sensitive and intimate details regarding a person’s life. It reveals details about an individual’s physical and mental well-being, potentially including sensitive conditions or infections that individuals may wish to keep private due to fear of discrimination, and social ostracism due to prevailing taboos and stigmas surrounding several health conditions. For example, the disclosure of one’s HIV status, or any other venereal disease (STDs/STIs), has often led to devastating consequences for the individual in a social, reputational, and economic manner. [8] Similarly, the disclosure of any health-related conditions or procedures where fear of prosecution is attached has far-reaching consequences. For example, the leak of a medical dataset of women obtaining abortions in a legal jurisdiction where it is criminalized. [9]

Data Storage, Transfer, and Privacy Conditions under the ABDM

Under the ABDM, a Draft Health Data Management Policy (‘Policy’) has been released by the National Health Authority, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [10] This specifies the collection, storage, retention, and transfer policies of health data pertaining to the ABDM. It is strongly centred around allowing the data principal to reclaim control and agency over their health data and retain autonomy over its collection, transfer, processing, etc.

First and foremost, it outrightly prohibits publishing, displaying, or publicly posting any personal health information. [11] A database, or any records therein, which have been processed under this Policy can only be made public in an anonymized/de-identified and aggregated form. [12]

Further, the Policy expressly denies any Health Information Providers (HIPs) from collecting or processing the personal data of a data principal without the consent of a data principal. Further, data can only be transferred to be shared with Health Infomation Users (HIUs) on the express consent of the principals, in compliance with the policy, and only for the specific purposes and duration specified therein.

As per clause 9.2. of the policy, consent must be:

- Free, under the standards of Section 14 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872;

- Informed;

- Specific;

- Clearly given; and

- Capable of being withdrawn at any time.

A data principal can only collect and process personal data for purposes as specified by the NHA, related to the health of an individual, or any incidental reasons thereto, all of which must be within the context and circumstance relating to the collection of the personal data, meeting the purpose limitation.

Clause 10 requires the provision of a privacy notice, in a clear and conspicuous manner, to the data principals. This must be done prior to obtaining the data from the principals and subsequently for the processing of personal data for a previously unspecified purpose or during any changes to the privacy policy. It may contain the following:

- Nature and categories of the personal data collected;

- Purposes of processing personal data;

- Methods and mechanisms for collecting personal data;

- Identity and details of the Data Fiduciary involved;

- Identity and details of any parties with whom the personal data might be shared, if applicable;

- Rights of the Data Principals;

- Mechanisms in place for the enforcement of such rights;

- Period of retaining the personal data;

- Identity and details of a point of contact to address a data principal’s grievances, inquiries and clarifications.

Despite the controlled approach for personal data, anonymized data can be shared for the purposes of facilitating health and clinical research, academic research, archiving, statistical analysis, policy formulation, the development and promotion of diagnostic solutions, and such other purposes as may be specified by the NHA. [13] It goes beyond this to identify the potential risks of re-identification or de-anonymization of anonymized data by prohibiting such processes, whether knowingly or unknowingly. [14] This is the first piece of state paper that recognizes this very real risk, that de-anonymization is an accessible and feasible process. This point of view has been successively excluded from all the versions of the draft data protection regulations (personal and non-personal), as well as the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, Justice Sri Krishna Committee Report and the Joint Parliamentary Committee Report.

How does the DEPA Holistically Address the Privacy Risks in the Health Sector?

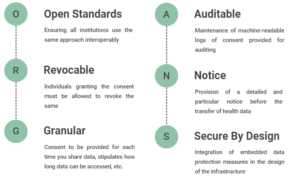

The DEPA adopts a Patient-centric approach, where access controls are concentrated with the patient to determine the terms of consent granted. As per the DEPA handbook [15], the following principles are to be followed while regulating consent:

OPEN STANDARDS, REVOCABLE, GRANULAR, AUDITABLE, NOTICE, AND SECURE BY DESIGN.

Explicit and informed consent is imperative for all information processing requirements under the DEPA, to the extent that in its absence, the sharing of health data is prohibited. [16] It is not only applicable to “data collected at each touch point and encounter but to the data relating to the entire Electronic Health Record” [17] both in a longitudinal manner (time) and latitudinal manner (record/instance). Establishing data ownership with patients, the state entities and decentralized databases are merely temporary custodians for patients’ data, with limited accessibility over the data. This is maintained under a trust-based relationship on behalf of the patients.

Data Principal Empowerment

Moreover, in the name itself, the DEPA aims to empower data principals by giving them more control and autonomy over the transfer of their data. It ensures that safeguards and protectionist measures are followed in the consent and notice mechanism, which are presently absent. The role of data principals is enhanced in health information exchange and is brought to the forefront to ensure that the ABDM is executed as a patient-centric model. By providing the right to grant granular consent, clarity on all the particulars of the health data required, the parties involved in the process, the right to control the duration of this access and the right to deletion, it actively grants rights to data principals. Further, it discredits and rejects the collection of deemed or implied consent and focuses on informed consent to avoid consent fatigue. Through this, the DEPA also standardizes the process of consent collection and management, making it more efficient and trustworthy.

Privacy By Design

From a tech infrastructural perspective, the DEPA lays a heavy reliance on privacy by design, through the integration and embedding of data protection measures in the data processing procedures. It ensures privacy through technical and organizational means, from its initial design phase and consistently throughout the entire lifecycle. This is visible in practice in the way that DEPA creates separate pathways for separate categories of data. For example, it prohibits publishing any data that isn’t anonymized or de-identified. In addition to this, it has been constructed in a manner to decentralize the storage of data. It is only permitted with the originators/creators of that data, i.e. HIPs and data principals, and not with the users or processors of that data, i.e. HIUs or HIE-CMs. Also, by enforcing the principle of minimal data sharing, retaining access controls with the data principals, and adopting transparency measures, the privacy of the user is fundamentally intertwined with the DEPA.

Consolidation and Standardization of Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

Presently, health data exists with over 50 lakh healthcare professionals and over 12 lakh healthcare facilities, all in different standards and formats on different platforms completely. [18] This makes the seamless exchange of health data between different healthcare providers, hospitals and systems a herculean task. Such impediments hinder effective data-sharing practices with multiple patient profiles existing on different and fragmented databases.

The introduction of the DEPA makes this process a lot more efficient by functioning on consolidating ABHA accounts. It ensures consistent and standardized storing of health data, enhances the economic and social values of data, and makes it a lot more usable, as uniformity increases utility. Further, all of the data channelled through the DEPA must be authenticated by DigiLocker, ensuring that all health data that exists in the digital ecosystem is verified and accurate data. This is an alarming concern in a country with rampant medical document forgery practices and unlicensed healthcare providers.

Security Risks and Scalability Restraints

To address the security risks posed to health data under the ABDM, the DEPA avoids the centralization of health data and stores it in a decentralized and fragmented structure. The most obvious benefit of such structures is that it becomes more difficult for cyber attackers to breach them and reduces the risk of a large-scale breach. Further, they are in perfect alignment with the principles of data empowerment as they give patients more ownership and control over their health data. This addresses all scalability issues as a decentralized approach can be more scalable and cost-effective than a centralized model. We note this with more and more health-tech companies, healthcare providers, consent managers, etc. becoming ABDM compliant.

Compliance with Existing Regimes and Standards

Lastly, the DEPA is designed to be compliant with India’s vision of a data protection legislation, in addition to the Information Technology Act 2000, Aadhar Act 2016, and the rules and regulations notified thereunder. Rather, it complements the above by providing a much more far-reaching, expansive, and holistic approach toward privacy and data protection. It is also compliant with the most advanced privacy standards on health information, such as the ISO/TS 17975:2015 ‘Health Informatics ‐ Principles and data requirements for consent in the collection, Use or Disclosure of personal health information’. [19]

Shortcomings

No large-scale digital transformation comes without its set of challenges and shortcomings, especially in India’s public sector.

Despite the ABDM being privacy-pro at its core, the incidents and reports of involuntary Ayushman Bharat Health Accounts (ABHA) registrations are just mounting with time. [20] In numerous cases, patients have found ABHA numbers on their vaccination certificates, that weren’t only generated without their consent, but even without their notice. The numbers show us that the data required to create these involuntary ABHA numbers were taken from PMJAY and CoWIN databases. There is a direct overlap between the spike in ABHA registration with the spike in CoWin vaccine rollout, from March-Sep 2021, and PMJAY registration, in January-March 2022. [21]

Further, the conversation of whether true, real, and conscious informed consent can be ever obtained in a country with alarmingly low literacy rates (let alone digital literacy), is futile. The DEPA or the ABDM refuses to address the efforts undertaken by them to make their services accessible and functional in low-literacy, or other disadvantaged, groups. Is it possible that this rapid digitization, supported by the DEPA, makes healthcare services even more inaccessible by widening the digital divide? The phenomenon of intervention-generated inequalities is not a new one for socio-technological solutions.

Moreover, there exists an inherently skewed power equation in the doctor-patient relationship, due to informational inequality. Combining this with lower sensitization towards consent and its implications, the health infrastructure falls short of making consent-giving more informed in reality.

In Conclusion

From a theoretical point of view, concerns regarding data disclosure and sharing in the health sector form a privacy paradox. The free and unfettered flow of health data directly benefits data principals in innumerable manners, from providing a more accurate and precise diagnosis to even targeted insurance schemes. However, this should not downplay the obvious risks associated with this.

The attitudes of patients toward sharing their personal health information have a direct effect on the design and architecture of future health information systems. [22] Hence, it is essential that through legislative as well as institutional reform, the need for informed choice and consent is concretized. Nevertheless, complex and diverse demographics have complex and diverse data needs. Shortcomings are inevitable in an attempt to homogenize and digitize healthcare services and the functioning of healthcare providers for India’s complex and diverse population.

Footnotes

[1] Anita Allen, Privacy and Medicine, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2011), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2011/entries/privacy-medicine/.

[2] Cost of a Data Breach: Report, IBM Security (2023), https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/E3G5JMBP.

[3] Infra.

[4] Healthcare Data Breach Statistics, The HIPAA Journal (2023), https://www.hipaajournal.com/healthcare-data-breach-statistics/.

[5] Paul Stanley, The Law of Confidentiality: A Restatement, OXFORD-HART PUBLISHING (2008), p. 49 (at 51).

[6] Roy McClelland and Colin M. Harper, Information Privacy in Healthcare – The Vital Role of Informed Consent, 29 EU. J. OF HEALTH LAW 1 (2022).

[7] Supra Note 18.

[8] See HIV Stigma and Discrimination in the World of Work: Findings from People Living with HIV Stigma Index, International Labour Organization (Jul. 2018), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_635293.pdf

[9] See Safia Samee Ali, Prosecutors in States where Abortion is now Illegal could begin building Criminal Cases against Providers, NBC News (Jun. 25th, 2022), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/prosecutors-states-abortion-now-illegal-begin-prosecute-abortion-provi-rcna35268.

[10] Ayushman Bharat Digital Health Mission: Draft Health Data Management Policy, National Health Authority (Apr. 2022), https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/Draft_HDM_Policy_April2022_e38c82eee5.pdf.

[11] Supra Clause 31.1.

[12] Supra Clause 31.2.

[13] Supra Clause 29.1.

[14] Supra Clause 29.3.

[15] Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture: Draft for Discussion, NITI Aayog (Aug. 2020), https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-09/DEPA-Book.pdf.

[16] National Digital Health Blueprint, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Oct. 2019), https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/ndhb_1_56ec695bc8.pdf.

[17] Infra.

[18] A Brief Guide on Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission and its Various Building Blocks, National Health Authority (2022), https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/ABDM_Handbook_19_10_2022_24c5078481.pdf.

[19] National Digital Health Blueprint, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Oct. 2019), https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/ndhb_1_56ec695bc8.pdf.

[20] Tabassum Barnagarwala, How India is creating digital health accounts of its citizens without their knowledge, Scroll.in (Aug. 27th, 2022), https://scroll.in/article/1031157/how-india-is-creating-digital-health-accounts-of-its-citizens-without-their-knowledge#:~:text=As%20a%20monitoring%20and%20evaluation,on%20one%20platform%20for%20easy

[21] Infra.

[22] Richard Whiddett, Inga Hunter, Judith Engelbrecht, Jocelyn Handy, Patients’ Attitudes Towards Sharing Their Health Information, 75(7) INTL. J OF MEDICAL INFORMATICS 530 (2006).