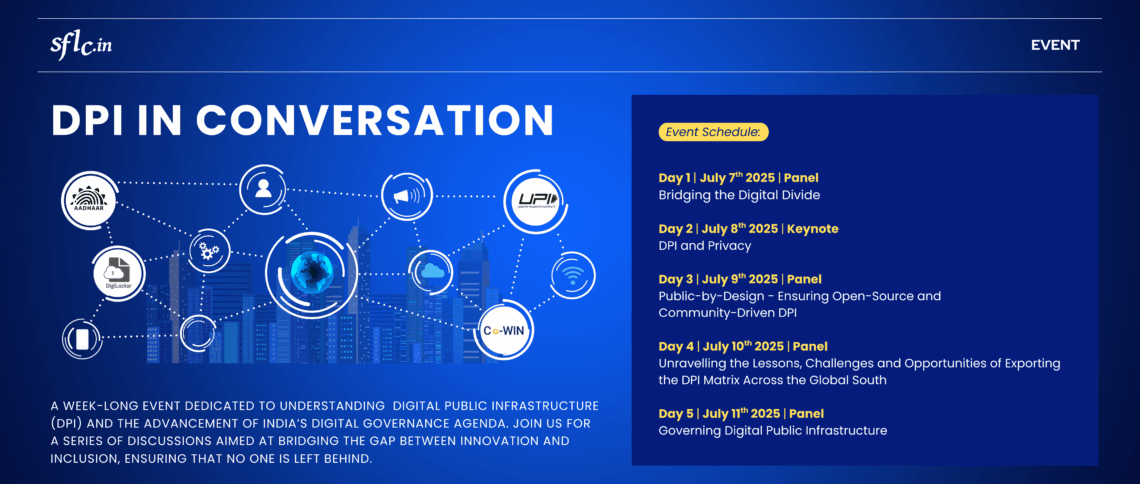

The Software Freedom Law Center India (SFLC.in) hosted “DPI in Conversation”, a week-long online event, from July 7–11, 2025. This event was designed to foster a deep and comprehensive dialogue on the rapidly evolving landscape of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) in India and the global stage.

DPIs are foundational digital systems, like UPI for payments and Aadhaar for identity, that are reshaping how citizens interact with the government, access essential services, and participate in the economy. As these systems become more integrated into our lives, they raise critical questions about privacy, data security, equity, and governance.

To navigate these complexities, “DPI in Conversation” brought together leading voices from technology, law, media, and civil society. Through a series of expert-led panels and discussions, the event delved into the nuances of DPI implementation across various sectors. The conversations explored both the transformative potential and the inherent challenges of these systems, examining their impact within the Indian context and their growing influence on the global stage.

Day 1: Panel Discussion: Bridging the Digital Divide

The opening session of DPI in Conversation brought together a sharp and critical panel to discuss one of the most pressing issues of our time, India’s growing reliance on Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), and its impact on digital inclusion, accountability, and citizen rights. The stakes were clear: 15 years after Aadhaar’s launch, has its promise of reform and inclusion delivered, or has it further widened the digital divide?

Prof. Reetika Khera, who has tracked the Aadhaar project since its inception, opened the discussion with striking candor: “While Aadhaar was initially promoted as an anti-corruption tool, a Trojan horse for systemic reform, in reality, it has created more barriers than benefits.” She recounted her gradual disillusionment, recalling how beneficiaries first faced three main hurdles: enrollment, database linkage, and repeated authentication. “Today, those hurdles have multiplied. The reality is an endless cycle of mandatory updates, lost card retrievals, and what I call ‘mock consent,’” she said.

She raised the plight of frontline workers, especially in states like Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh, whose core jobs, such as providing maternal healthcare, are increasingly replaced by “geo-tagged” data entry. “When the network fails or the system glitches, it’s the worker who is punished, not the technology.” Crucially, she critiqued Aadhaar’s erasure of institutional memory: “Without proper documentation, it’s impossible to counter the powerful narratives spun by Aadhaar’s backers. The voices of the marginalized are rendered invisible by design.”

Independent law researcher Usha Ramanathan took a step back to challenge the DPI ecosystem itself. She stated, “The DPI project has turned public data into a tradable asset. Citizens, especially the poor, are offering up their data instead of material wealth.” She cited key legal shifts, especially since 2019, that have “handed companies greater power to use UID-linked data, even offline.” The original vocabulary of “good governance” has, she noted, quietly disappeared from official pronouncements. “Aadhaar’s biometric system routinely fails, and the poor disproportionately pay the price. Originally billed as a tool for governance, Aadhaar is now central to building a digital economy, not serving citizens’ welfare.” Is “Aadhaar 2.0” a genuine transformation? Ramanathan was skeptical. “It’s just a rebranding of the same old problems. The legal changes are meant to support outcomes already decided behind closed doors.”

Aditi Agrawal, drawing on her journalistic experience, challenged both the definition and the narrative: “What counts as Digital Public Infrastructure today? It’s so vague, it covers everything from DigiYatra to FASTag to UPI and IndiaStack. The lines between DPI, Digital Public Goods, and platforms like ONDC are blurred by design.” She referenced the G20 New Delhi Declaration and think tanks like Carnegie: “There’s a growing narrative that DPI will solve everything, even global challenges like climate change. That’s not just optimistic, it’s out of touch with reality.”

Agrawal recounted a telling example: “Anganwadi workers in Delhi use an app that compresses photographs so much that key health indicators are lost. Hype gets in the way of usability.” The system, she argued, often works for service providers rather than users: “UPI has made life easier, but mostly for businesses. ONDC tries to connect buyers and sellers, but doesn’t address the underlying infrastructure issues.”

Watch full session here:

Day 2: Key Note: DPI and Privacy

On day 2, Ms. Renata Avila, CEO of the Open Knowledge Foundation, delivered a keynote address on DPI and Privacy.

Renata began her remarks by expressing her gratitude to the organizers, noting that the work of the host organization had long served as a source of inspiration in her career. She reflected on how India, despite its deep inequalities and democratic complexities, remains uniquely positioned to build an ambitious technology infrastructure. She credited decades of consistent national investment in math, science, and education for this, especially the hard work of teachers, parents, and institutions in creating a skilled and capable population. She contrasted this with the situation in her home region of Latin America, where structural limitations have made it difficult to equip citizens with the digital skills needed to navigate the future.

Renata noted that India has the capacity to forge a new digital path that is neither defined by Silicon Valley nor by authoritarian surveillance regimes. However, she cautioned that instead of building that third path, many countries, including India, are dispersed and feed it into a system, two-way system that is only increasing the things that we do not want to see reproduced at scale in the world. Her critique, she emphasized, came from a place of deep admiration and concern, a hope that India would use its technological capacity to reverse course and build something more just.

Watch full session here:

Day 3: Panel Discussion: Public-by-Design – Ensuring Open-Source and Community-driven DPI

Prasanth Sugathan, Legal Director at SFLC.in and moderator of the session, opened the discussion with his opening statement. He said that the government has been increasingly turning to Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) to deliver essential services. The promise of ‘open source’ software has been the key narrative. This leads us to the question of what Open Source truly means and what Open Source principles refer to. In this context, ‘Open Washing’ is when Open Source is used but in violation of its intended meaning. This warrants attention and leads one to question whether DPI initiatives live up to the ideas of transparency and are participatory and democratic.

While shedding light on South Africa’s initiative on DPI, Ms Desire Kachenje (Senior Principal (Investment), Co-Develop) said that there is a need to define a public good and think about how countries can maintain it even when there is public-private alignment. There is a need for a public good that meets safety and inclusion requirements.

Highlighting India’s stand on open source and DPI, Ashish Aggarwal (VP and Head of Government Policy & Engagements, Nasscom) stated that the open source aspect is more of a directional conception; it does not mean that everything is open source. It is not just about technology and a way forward, but also looking back to say, how do we put together a governance framework around it? Actual value will happen, and scalability and adoption will be critical. The Identity, Payment, and Data Exchange DPIs are fantastic foundational pieces…. There is a lot of interaction from the RBI regarding mechanisms for engagement. The government and regulators reach out to try and source solutions so that systems can reach out to a large audience. Even though the government has not built it out, it is private, and there is collaboration.

While answering a question, Sai Rahul Poruri (CEO, FOSSUnited) sketched the broader context: “The Internet itself is the original DPI, federated by design; no single entity controls it. The success of Open Source came by incentivizing communities, making systems better by enabling anyone to find issues and propose fixes.” Today, he fears, reinvention and complexity are replacing careful evolution and collaborative debugging: “We’re seeing repetition of the same mistakes, without working groups, broad-based standards, or platforms for public challenge. The reason for Open Source’s vibrancy, people could find, report, and fix problems, isn’t always present in DPI. We need structures for capacity-building and social engineering tricks, not just tech contracts.”

Watch full session here:

Day 4: Panel Discussion: Unravelling the Lessons, Challenges and Opportunities of Exporting

The DPI matrix across the Global South

As the DPI in Conversation series entered its 4th day, the spotlight turned to two critical questions resonating across the global South: Can Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) be engineered to cultivate real public value, accountability, and sovereignty? And how do we balance the vital roles of both state and private sectors, without sacrificing inclusion, fairness, and individual rights?

With Aarathi Ganesan, Manager, Public Policy, TQH, and Dr. Dovan Rai, Director of Research & Development, Body & Data, as key resource persons, this session mapped out the promise and pitfalls of public-private participation in shaping national digital destinies, using India and Nepal as vibrant case studies.

Aarathi and Dr Rai tackled the nuanced role of the private sector in DPI development. Both underscored that while private sector participation is practically necessary, especially where state capacity is thin, it must be designed to foster actual competition and broad participation.

Aarathi noted that “DPIs should use the private sector’s dynamism to create open, competitive ecosystems, not new monopolies. The risk is that without careful regulation and transparent authorizing structures, private companies may end up with disproportionate control over systems meant to be public.”

The session delved into the gulf between mandatory adoption of digital IDs and real, informed choice, especially where digital literacy and administrative education are limited.

Dr Rai emphasized that “People often don’t know what the new ID is for, how it differs from their citizenship documents, or what the risks are. Even implementers at local levels lack coherent messaging. Better top-down vision, education, and communication must precede, not follow, tech rollouts.”

Watch full session here:

Day 5: Panel Discussion: Governing Digital Public Infrastructure

The final session in the ongoing DPI in Conversation series unfolded with a reflection on how digital public infrastructures (DPIs) intersect with governance frameworks, a critical nexus shaping equity, privacy, and sovereignty, with a panel discussion on the Governing Digital Public Infrastructure.

Yasodara Córdova, Independent Researcher, opened the session by drawing on her long experience working with DPIs, including their precursors, emphasizing their role in transforming cumbersome, in-person processes into more streamlined digital governance systems. She cited India and Brazil as pioneering examples, but noted the complex negative externalities such as identity fraud aided by deepfakes. Yasodara highlighted that the next frontier for DPI governance must be cybersecurity, not narrowly as a national security matter, but as a broader civil right intertwined with privacy. Regulations must embed privacy and cybersecurity engineering into the very DNA of DPI systems.

Adding a global comparative lens, Luca Belli (Professor, FGV Law Schoool & Coordinator, Center for Technology & Society) shared insights from CyberBRICS, a project comparing DPI initiatives across BRICS countries. He underscored two essential dimensions of DPI governance: how these infrastructures shape digital transformation and how they embody digital sovereignty. He praised examples like India’s UPI and Brazil’s Pix as reclaiming autonomy from global finance giants, highlighting crucial principles: user transparency, non-discrimination, cybersecurity risk management, and expanding meaningful connectivity. Yet, he also noted practical limitations, including scaling challenges.

Disha Verma (Program Manager (APAC), Tech Global Institute) offered a critical reflection on the political economy of DPIs in India, emphasizing their intense politicization under techno-nationalist agendas that stifle dissent and vital research. She expressed concern over the shift of governance dialogues towards abstract, European-centric language, while community harms, such as surveillance, profiling, and electoral manipulation, remain under-addressed. She called for spaces for frank public debate and civic participation, even as internet freedoms shrink globally.

Finally, Soujanya Sridharan (Senior Manager, Aapti Institute) brought grounded perspectives from the Indian DPI ecosystem. Recounting varied innovation pathways, from the government-driven Aadhaar and UPI to emerging systems like ONDC, she underscored the core role of deliberate government policymaking underpinning such initiatives. She stressed the importance of institutional infrastructure, data transparency (such as NPCI and UIDAI data), and the need to critically engage with these datasets to understand digital access and exclusion. She also highlighted emerging research resources and urged a sharper focus on accessibility and exportability of innovations.

Watch full session here:

Concluding remarks:

DPI in Conversations week highlighted DPIs have the potential to transform governance, service delivery, and economic participation, but their success hinges on how the DPIs are designed, implemented, and regulated. DPIs risk reinforcing inequality, exclusion, and unchecked surveillance if left without strong safeguards. The discussions made it clear that technology alone cannot guarantee positive outcomes; the real determinant is the framework of governance, accountability, and public oversight that surrounds it.

Cross-country collaboration, particularly within the Global South, offers an invaluable opportunity to exchange not only success stories but also hard-learned lessons from failed or problematic implementations. Countries facing similar socio-economic and infrastructural challenges can learn from each other’s experiences in balancing state and private sector roles. Ultimately true progress and future of DPIs will depend on the ability of states to develop DPIs that’s transparent, have robust privacy protections, and genuine adherence to open-source principles. These systems must be designed to expand access, not create new barriers, ensuring that benefits reach the most marginalized communities. To achieve this, civic participation cannot be an afterthought; it must be embedded from the earliest stages of policymaking and implementation, allowing those directly affected to shape how DPIs evolve.