Introduction

On 30th July, the EU Artificial Intelligence Office launched a public consultation on trustworthy general-purpose AI models. The call encourages participation from a diverse range of stakeholders – academia, industry representatives, independent experts, civil society organisations, rights holders and public authorities. In contrast, India has witnessed an increase in closed door consultations that tend to confine the process to only a particular set of stakeholders. For instance, the Broadcast Services (Regulation) Bill, 2023 (“Broadcasting Bill”) has reportedly undergone revisions. However, only select stakeholders have received copies of the Broadcasting Bill after signing undertakings to not reveal the drafts public. Furthermore, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (“MIB”) has not published the comments given by all stakeholders to the initial draft of the Broadcasting Bill as required under the Pre-Legislative Consultation Policy (“PLCP”).

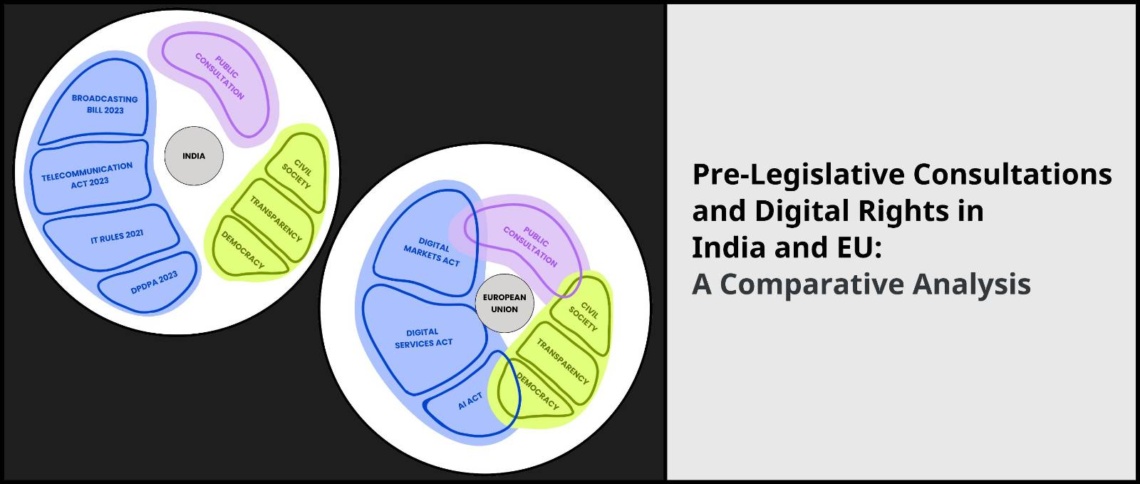

This blog post analyzes the difference in approaches to pre-legislative consultations between EU and India. Recently, the Government of India has passed laws like Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 (“Intermediary Guidelines 2021”) and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 (“DPDPA”) without extensive pre-legislative consultations. This results in the basic modalities of democracy being subverted. Such laws further distance themselves from the will of the people and their fundamental rights instead of being closer to them. This blog post highlights how such an approach could widen the gap between rights and laws in India.

The gap between practice and policy: Comparing consultation processes in India and EU

Notably, the Government of India adopted the PLCP in 2014. It prescribes that every department/ministry to publish proposed legislation for public consultation and scrutiny by all stakeholders. Moreover, the concerned department/ministry must also publish the comments/feedback received on its website along with responses. Public consultations hence provides an avenue to enter into fruitful discussions, opportunity to address concerns, seek clarification and to rectify errors/loopholes in draft laws. However, the catch in PLCP is that it provides exceptions to government bodies, paragraph 11 of the PLCP states that if a department/ministry is of the view that public consultation is not feasible or desirable it may record such reasons to avoid public consultation. This exception provides enough leeway and justification for the government to avoid or lessen public engagement.

There have been several other instances in recent times where the departments/ministry have departed from following the guidelines under PLCP. Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology refused to disclose the feedback on the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022. Similar issues were also reported prior to enactment of the Telecommunication Act 2023.

In fact, the Central Government notified the Intermediary Guidelines 2021 in the official gazette. However, the Government is required to table such a legislation in both Houses[1]. Such occurrences undermine the public’s trust in government as interested stakeholders are denied an opportunity to discuss and raise their concerns through the pre-legislative consultation process. Such selective consultation practices also breeds uncertainty among stakeholders regarding the substantive nature and impact of the proposed legislations.

In the EU, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Better Regulation Agenda work together to ensure participatory democracy through public consultation which is transparent, accountable and inclusive. Most EU Member States also have a detailed consultation process prior to enforcement of laws. The European Commission has its own dedicated website where citizens, experts and special interest groups can submit feedback on legislative proposals. For example, the public consultations for the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act involved a diverse group of stakeholders, ranging from civil society organisations to businesses and non-governmental organisations. Civil society was the most active stakeholder group — contributing 66 per cent of the 2,863 responses received during the consultation.

Conclusion

Public consultations are thus essential in democratic societies. Such consultations are even more crucial for laws that intend to govern digital rights and freedoms. Given that the Broadcasting Bill deems to control, censor and regulate free speech, jeopardize artistic freedoms and aims to place obligations on content creators, journalists, writers, artists and other diverse groups, it is crucial to engage a wide range of stakeholders instead of selective groups. A democratic system of government must encourage diverse stakeholders through public consultation. Adhering to the PLCP will ensure thorough analysis, better transparency, and fair evaluation of various viewpoints before the law is enacted. Furthermore, the MIB should also publish the Broadcasting Bill in regional languages to give regional stakeholders a fair chance to access public consultation. Moreover, following a transparent approach to public consultations is also beneficial for the government to strengthen the public’s trust in a democracy.

[1] Information Technology Act (2000), sec 87(3) requires every rule made by the Central Government to be tabled in both Houses of the Parliament as soon as possible.