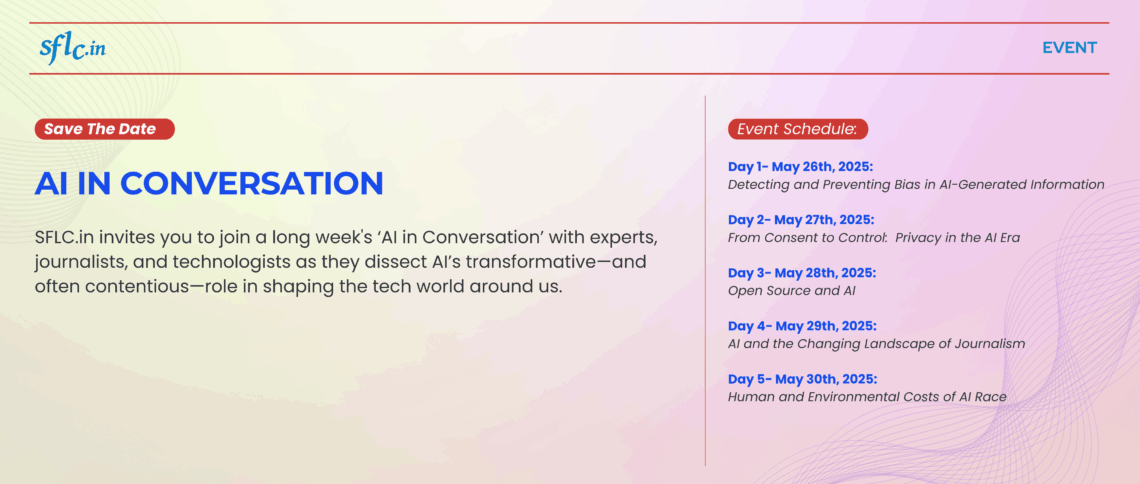

Software Freedom Law Center India (SFLC.in) organized “AI in Conversation”, a week-long online AI in conversation week (May 26–30, 2025), bringing together experts from tech, law, media, and civil society to understand the nuances of Artificial Intelligence in the Indian context across different verticals.

SFLC.in, which works at the intersection of law, technology, and human rights, is already actively engaged in AI policy through tools like its AI Elections Tracker (monitoring AI use in political campaigns) and the AI Policy Tracker (documenting evolving government policies). This symposium furthered its commitment to multi-stakeholder engagement by exploring the implications of AI across five key themes:

As a speaker noted, “AI is not a distant science fiction anymore, it is embedded in our everyday experiences: social media feeds, search predictions, streaming recommendations, voice assistants, and navigation apps all rely on AI-driven systems. AI shapes much of how we interact with technology today, often in ways we do not even notice”. Given this ubiquity, SFLC.in emphasized that responsible development in AI cannot wait any longer.

The event covered six themes:

- Building Responsible AI Models

- Privacy in the AI Era

- Open Source and AI

- Free Speech and AI

- Use of AI in Indian Journalism

- The Human and Environmental Cost of AI

Day 1: Building Responsible AI Models – Opportunities and Challenges

The opening keynote by Mr. Praveen Chandrahas (Swathantra Software Movement) explored India’s digital and linguistic divide in AI. Chandrahas argued that most leading AI models (LLMs) like ChatGPT or Claude are trained on vast amounts of internet data in a few “colonial” languages (English, Spanish, etc.), leaving Indian languages severely underrepresented. He noted that GPT-4’s latest version is trained on trillions of word tokens, whereas scraping all Indian-language content available online might yield only a few billion.

In practical terms, every Indian language (including Hindi) is “digitally resource-poor”; there simply isn’t enough text, audio, or labeled data online to train robust AI models. This gap is significant because India’s literacy rate (e.g., ~75% in Telangana) far exceeds English proficiency (perhaps only ~20% in that state). In other words, building AI for India requires creating models that understand Indian languages and contexts, not just English. Mr. Chandrahas warned against “blindly replicating” Western approaches. Instead, he emphasized that India needs its own path to democratic AI: systems built through broad participation and tailored to local needs.

He highlighted two major challenges: data and computers. First, language data is scarce. For example, Mr. Chandrahas described crowdsourced efforts to collect Telugu content: volunteers conducted a “data-thon” to convert scanned Telugu children’s books into text, and another project (“Guntuka”) was launched to gather voice samples. These community-sourced datasets helped train AI models for Telugu story generation and speech recognition. Such initiatives demonstrate how communities can play a vital role in building local datasets.

Second, computing power is highly concentrated. Training an LLM typically requires hundreds of thousands of powerful GPU machines that cost millions of rupees and face import tariffs. Chandrahas pointed out that if “the only way to build an AI is by having access to 100,000 high-end GPUs, that’s not democratic, nobody will have access to these except the ultra-rich or mega-corporations.”

To make AI development more equitable, he argued that India must democratize both data and hardware. This includes exploring creative solutions such as algorithmic improvements, shared infrastructure, energy-efficient training, and more so that research labs, startups, and universities can meaningfully contribute.

Watch the complete session below:

Day 2: From Consent to Control – Privacy in the AI Era

Day 2 featured a panel discussion moderated by Mr. Prasanth Sugathan (SFLC.in), with Ms. Namita Maheshwari (Access Now) and Dr. Gus Hosein (Privacy International) as panelists. The panel examined the evolving landscape of privacy, consent, and surveillance in the age of AI.

The panel discussion explores the complex intersection of artificial intelligence (AI), privacy, and data protection in the evolving digital landscape. As AI technologies proliferate from facial recognition in public spaces to large language models trained on scraped internet data, concerns about the erosion of privacy and the inadequacy of existing legal frameworks become urgent. The panelists, experts from legal, policy, and human rights backgrounds, emphasize that traditional data protection concepts like user consent are increasingly ineffective in the AI era. Instead, there is a call to redefine privacy and data governance through democratic accountability, transparency, and robust regulation.

The conversation highlights types of AI raising privacy concerns:

Generative AI systems that learn from vast datasets without consent, predictive AI is often used in policing and warfare, and AI-driven detection systems like facial recognition are deployed without public consent. The panelists critique the overreliance on consent as a control mechanism, pointing out that pervasive data generation and surveillance technologies undermine meaningful user control.

Encryption was another focal point of the discussion. As an encryption policy expert, Ms. Maheshwari pointed out that AI is a double-edged sword for digital security: while it can help protect data, advanced AI tools can also be used to undermine or break existing protections. The panel explored proposals like client-side scanning (which intercepts content before it’s encrypted and sent), raising concerns that integrating AI into messaging platforms threatens actual end-to-end encryption. Maheshwari stated bluntly: “AI and end-to-end encrypted systems are fundamentally incompatible,” as AI-based scanning or data collection inherently weakens user privacy.

Government deployment of AI in public services raises additional risks, especially concerning vulnerable groups like children, whose data can be exploited for profiling and intrusive surveillance.

A recurring theme was the urgent need for stronger regulation. Both panelists agreed that India lacks robust enforcement of its data protection laws. “We have a law, but it’s not enforced,” Maheshwari noted. Without meaningful reforms, they warned, AI could amplify mass surveillance and systemic harm. Dr. Hosein emphasized that many countries, particularly in the Global South, are racing to adopt AI technologies without updating outdated privacy laws or surveillance frameworks. Finally, the experts warn against industry-led self-regulation, calling for enforceable legal frameworks that hold both corporations and governments accountable. They view AI as a critical moment to advance privacy protections and democratic oversight, cautioning against deregulation trends that could empower powerful tech monopolies and authoritarian governments.

The discussion concluded with a strong call for active public engagement in AI policymaking. As the speakers stressed, ensuring rights-respecting AI governance requires more than just top-down tech deployment; it demands democratic participation, accountability, and regulatory foresight.

Watch the complete session below:

Day 3: Keynote 1 Open Source and AI

Ms. Nithya Ruff emphasized that open source is essential for building trustworthy and equitable AI systems. She critiqued Big Tech’s “black-box” models, noting they are often unfit for diverse global contexts. With countries increasingly advocating for “sovereign AI” AI that reflects local languages, data, and values, Ms. Ruff argued that AI should be seen as “cultural infrastructure”. When design and training are concentrated in one region, other cultures risk exclusion. She highlights how open source software has become the backbone of modern technology, enabling innovation, reducing costs, and fostering collaboration across industries. Despite AI’s recent rise as a consumer-facing technology, much of it remains proprietary due to high costs and concerns about misuse. However, the emergence of open-source AI models like DeepSeek is challenging this norm by demonstrating that open, collaborative approaches can deliver competitive performance with fewer resources.

Ms. Ruff presented open-source AI as a viable alternative:

- Transparency and auditability: Open models allow scrutiny for bias, security flaws, and ethical issues.

- Local adaptability: Open models can be fine-tuned with local data to align with regional needs.

- Collaborative innovation: A global “flywheel” of contributors can build upon shared tools, accelerating progress at lower costs.

She also points out challenges such as the lack of a consistent definition of “open” in AI, complexities around licensing due to AI’s data-centric nature, and the need for frameworks like the Linux Foundation’s Model Openness Framework and Open Model License to clarify what openness means in AI.

On regulation, Ms. Ruff observed a global trend toward transparency and open standards, citing the EU AI Act and recent executive orders. However, she warned that the term “open” is often misused – partial releases (e.g., code without training data or weights) fall short. True openness requires full reproducibility and open licensing. Organizations like OSI and the Linux Foundation are working to define these standards more rigorously.

Watch the complete session below:

Day 3: Keynote 2: Free Speech and AI

Rebecca MacKinnon, Vice President of Global Advocacy at the Wikimedia Foundation, focuses on free speech and human rights in the AI era. She explained Wikipedia’s role as a global knowledge commons and its symbiotic relationship with AI, as Wikipedia’s content is extensively used to train large language models (LLMs). Wikipedia’s freely available content forms a significant portion of the training data for large language models. This relationship highlights the importance of giving proper attribution to content creators and ensuring provenance is traceable. Without clear attribution, the public cannot verify the reliability of the information, increasing the risk of misinformation propagation. Wikipedia’s volunteer community governance model, which enforces strict content standards, serves as a microcosm for how human oversight remains essential alongside AI tools.

Ms. Rebecca stresses the importance of attribution, provenance, and transparency to maintain information integrity and public trust. She highlights the challenges posed by disinformation, information warfare, and governmental or corporate pressures that threaten free expression and the autonomy of volunteer communities maintaining platforms like Wikipedia.

Tackling AI-generated falsehoods via content takedowns is fraught with risks of misuse and censorship. Instead, regulators should focus on the underlying business models, particularly those incentivizing the spread of disinformation for profit, such as surveillance capitalism. Supporting public-interest digital commons and community-governed platforms like Wikipedia requires nuanced policies that protect their ability to thrive while holding bad actors accountable.

Ms. Rebecca argues for regulation to be grounded in human rights principles that protect freedom of expression, privacy, and community self-governance while addressing the risks of AI misuse. She advocates for distinguishing between commercial platforms driven by surveillance capitalism and public-interest projects like Wikipedia. Her team is developing AI-assisted tools to help editors detect misinformation, improve multilingual content, and preserve the quality of free knowledge. The conversation underscores the need for global solidarity in defending free speech norms amid rising censorship and misinformation, emphasizing that AI’s transformative power must be harnessed responsibly and inclusively. The fundamental human rights of free expression and privacy are also under heightened threat due to AI-driven disinformation campaigns, governmental censorship, and corporate pressures. Wikipedia’s experience shows that protecting volunteers’ anonymity and autonomy is essential for maintaining a trustworthy knowledge ecosystem. AI amplification of misinformation can drown out marginalized voices unless communities are empowered to maintain editorial integrity and self-governance, supported by robust legal and policy frameworks.

Watch the complete session below:

Day 4: AI and the Changing Landscape of Indian Journalism

The Day 4 panel brought together senior journalists Itika Sharma (Rest of World), Vineet Bhalla (Scroll.in), and Binayak Das Gupta (Hindustan Times), moderated by Suraj Singh (SFLC.in). They examined how AI tools are reshaping newsroom workflows, raising editorial and ethical questions.

A clear consensus emerged: human journalists remain essential. The panelists agreed that while AI can assist with routine tasks, it cannot replace core journalistic judgment. As Binayak Das Gupta explained, his newsroom follows a strict rule: “Please do not use AI to write or create any articles.” AI is used only for supportive work such as generating story summaries, transcribing interviews, or suggesting headlines and headline prompts. However, final editing, fact-checking, and narrative crafting are always handled by people. All panelists emphasized: “Human oversight and review is something we are not compromising.” In fact, Binayak noted that in 95% of cases, AI-generated content requires human correction. No current LLM can match a seasoned editor’s ability to write an accurate, compelling headline or spot nuanced errors.

The journalists shared examples from their own newsrooms. Ms. Sharma explained that at Rest of World, AI is used only “behind the scenes,” for example, to speed up research or suggest initial story ideas, but never to produce published copy. She stressed that every published story has a human author responsible for its content, in line with their principles of transparency and accountability. Mr. Bhalla, who trained as an “AI evangelist” through a Google journalism program, also found AI invaluable for sifting through data and generating leads. However, he strongly agreed: “There are certain core tasks of journalism – reporting, storytelling, and research that AI still can’t do.” For instance, covering a live protest or conducting interviews requires human presence and creativity.

Ethical concerns were also discussed. The panel warned about AI errors and biases. Mr. Bhalla shared how he once asked an AI tool to list immigrant tech founders, and it returned numerous incorrect names, highlighting how common AI hallucinations are. The panelists also noted the danger of undisclosed AI-generated content online, emphasizing that readers can often tell when a story was written by AI rather than a human expert. The economic implications of AI were also discussed, especially its role in pressuring journalists to produce more content faster, and a consensus emerged that AI should be viewed as a productivity multiplier rather than a substitute for journalistic labor.

To maintain trust, the speakers underscored the need for clear policies. For instance, Hindustan Times explicitly forbids AI-generated articles and uses AI only for editorial support tasks like proofreading.

Watch the complete session below:

Day 5: Human and Environmental Cost of the AI Race

The final session focused on often-neglected issues: the labor and environmental footprint of AI. Ms. Donna Matthew (Digital Future Lab) opened with a warning that the global AI boom carries serious real-world costs. She framed her talk around the “materiality” of AI, the physical infrastructure and supply chains behind every algorithm, and the social costs they entail.

Ms. Matthew highlighted that training and running AI models is extremely energy- and resource-intensive. Data centers powering AI consume massive amounts of electricity (often from fossil fuels) and require rare metals for servers. These centers also need millions of liters of fresh water for cooling. To illustrate, she cited a striking estimate: generating a single ChatGPT response uses about 500 milliliters of water just to cool the servers. Such figures reveal that behind the “cloud” of AI lies a significant environmental footprint.

Moreover, building AI hardware relies on mining metals like cobalt and nickel. These mining operations can devastate local environments and communities. Ms. Matthew described how processing minerals releases toxic sludge into soil and water, and how artisanal mines (common in places like the Congo, Indonesia, or the Philippines) often involve child or forced labor. For example, nickel mining in Indonesia has displaced indigenous people and contaminated fisheries. In effect, the global demand for AI components is outsourcing pollution and human rights abuses to the Global South.

In addition to raw materials, Matthew noted that AI’s energy demands are growing. As models become larger (with more parameters) and as “agentic AI” (AI that acts autonomously) spreads, electricity and water use will continue to rise. Yet, she lamented, companies rarely publish transparent data about AI’s emissions, making it difficult for policymakers to regulate.

Despite these costs, Ms. Matthew also acknowledged AI’s climate-positive promises, such as optimizing energy use or aiding disaster response. Her message was one of balance and accountability. She urged stakeholders to adopt a lifecycle approach: considering environmental and human impacts from design through disposal. That means conducting rigorous impact assessments of AI infrastructure, demanding corporate reporting on energy and water usage, and critically asking whether AI is even the right solution for a given problem. Simple mitigation steps can help: building smaller, purpose-specific models instead of gigantic general ones; minimizing unnecessary data collection; and strengthening cross-disciplinary collaboration so that technologists consider ecological trade-offs.

Watch the complete session below:

Conclusion

Across the week’s discussions, one theme shone through: AI must be shaped collectively, with attention to human rights, culture, and ethics. No single group, whether Big Tech, governments, or one nation, should dictate AI’s course. As Pravin Chandrahas urged, AI in India must become “democratic”, with broad participation in creating and accessing models. Echoing this, Nithya Ruff emphasized that models are now “culture infrastructure” and countries need AI that “reflects their own values”. In practical terms, this means embracing open-source development, inclusive data collection, robust privacy rules, and accountability in AI deployment.

SFLC.in’s role in convening these dialogues highlights the value of multi-stakeholder forums. By bringing technologists, policymakers, journalists, and researchers together, the series advanced a more nuanced public discourse on AI. Key takeaways include the need for transparency and oversight – in training data, algorithms, and their impacts – as well as the importance of local context in protecting linguistic and cultural diversity in AI. There was also a strong insistence on ethics and rights, including privacy, labor, and environmental protections.

As Day 4’s panelists put it, the essence of journalism – truth, accuracy, and human judgment – must guide AI use. Similarly, other sessions reiterated that AI systems should be open, accessible, and accountable to the societies they serve. In the end, the “AI in Conversation” series showed that navigating the AI era requires ongoing dialogue among all stakeholders.

Ultimately, the challenge ahead is not merely technological; it is profoundly human. AI will influence how we work, learn, communicate, and even perceive truth itself. If deployed carelessly, it risks deepening inequality and eroding trust. But if guided responsibly, it holds the potential to drive innovation, expand access to opportunity, and strengthen democratic resilience.

SFLC.in will continue to shape this conversation through policy research and advocacy. Policymakers, technologists, and citizens alike should heed these insights, ensuring that AI development remains a tool for the public good rather than an unchecked race. By putting people, rights, and sustainability at the center, India (and the world) can steer AI toward a future that benefits everyone.