The Indian Patent Office organised a stakeholder consultation on October 11, 2013 on the draft Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions (CRIs) issued by it. Mr. Chaitanya Prasad, Controller General of Patents, designs and trademarks, chairing the meeting emphasised that the purpose of the Guidelines is to bring consistency and uniformity in practice of all the patent offices in the country. A laudable attempt by the Patent office, indeed. However, what transpired in these discussions was a fierce attempt to re-ignite the discussion of patentability of software (something that the Indian Parliament had rejected in 2005) by the usual beneficiaries of such a system: the mutli national holders of patent thickets, lawyers, and patent agents. What was peculiar was the absence of small and medium level Indian players.

The attempt of the Patent office in coming out with these guidelines is a step in the right direction as it would help in reducing the inconsistencies in practice. SFLC.in submitted its comments to the patent office that focused especially on the legislative intent and the procedure for examination.

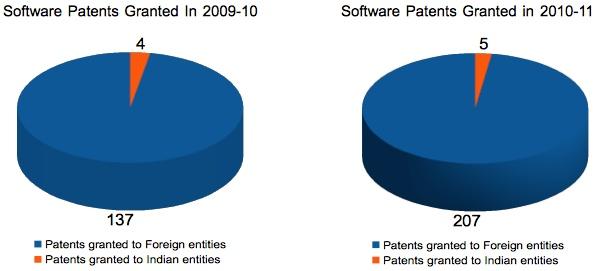

The Patents Act, 1970 has excluded “computer programmes per se” from the realm of patentable subject matter. However, in practice, patents continue to be granted irregularly in the field of software. A research conducted by SFLC.IN has revealed that 141 and 213 patents were granted in the area of computer related inventions in the years 2009-’10 and 2010-’11respectively, with the share of Indian companies in these patents being miniscule.

The stakeholder meeting was dominated by patent agents and industry bodies like NASSCOM, FICCI, CII, BSA and US-India Business Coalition with SFLC.IN and Knowledge Commons being the only vocal voices representing civil society. The heavy presence of foreign companies in a policy making discussion only arouses suspicion. Some of these companies have yet to make up their mind whether they exist in India or not as repeated court filings evince. Comments made by many of the patent law firms seemed to suggest that the meeting was about changing the law. In fact, a lawyer representing a leading law firm even commented that “the law is for the industry and that the law should protect the interests of industry.” It was intriguing how patent agents and lawyers, whose interests could only be to ensure more patent filing and litigation could represent the interests of the industry and project themselves to be the face of the country. We are curious to find out if the industry bodies such as FICCI and NASSCOM really took the opinion of the smaller players and startups before finalising their submissions that supported software patents as currently domestic players such as Micromax Informatics Ltd are in dispute with International holders of patents such as Ericsson.

SFLC.IN raised concerns about the comments raised about changing the law and clarified that the guidelines do not constitute law-making and that these can only work within the mandate of the law. We reminded the gathering about the legislative intent behind excluding “computer programmes per se” from patentability. An issue that has been decided by the Indian public through its elected representatives long ago but to the proponents of software patents, cognitive dissonance seems to prevail in this area like many others.

For those of you who are interested in actual facts:

The Government of India had issued the Patents (Amendment) Ordinance, 2004 that amended Section 3(k) of the Patents Act, 1970 as :

“(k) a computer programme per se other than its technical application to industry or a combination with hardware;

(ka) a mathematical method or a business method or algorithms”

The Patents (Amendment) Bill, 2005 which included this amendment to Section 3(k) was introduced in the Lok Sabha on March 18, 2005. Clause (c) of para 7 of Statement of Objects and Reasons of The Patents (Amendment) Bill, 2005 stated that a feature of the ordinance was to “modify and clarify the provisions relating to patenting of software related inventions when they have technical application to industry or in combination with hardware”.

After deliberations in both the houses of Parliament, the proposed amendment to Section 3(k) was dropped. The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005 repealed the Patents (Amendment) Ordinance, 2004.

The press release dated March 23, 2005 on the Bill by the Ministry of Commerce and industry states that “It is proposed to omit the clarification relating to patenting of software related inventions introduced by the Ordinance as Section 3(k) and 3 (ka). The clarification was objected to on the ground that this may give rise to monopoly of multinationals.”

A few industry representatives objected to our intervention by asserting on incorrect account of these proceedings and said that the Patent Amendment Bill, 2005 did not include the amendment to Section 3(k).

Thereafter started a tirade of moot arguments about the need for patentability of software as the discussion was merely about guidelines. The presence of Multinational companies with obvious agendas and U.S. and European centric arguments was of little surprise to the long time observers of this area of policy making. The representative from FICCI expressed their dissent on the restrictive interpretation of sec 3(k) in the guidelines which, according to them was in conflict with the statute. They pointed out that examples and illustrations as provided in the guidelines are contradictory and confusing in nature. They also requested to include details of what is patentable in the guidelines. They pressed that novel software in General Purpose Computers should be patentable. The Business Software Alliance started by advocating the requirement for a broader interpretation of sec 3 (k). They were of the view that the ICT industry needs protection for the Computer Related Inventions. They were of the view that it is not necessary to have a hardware restriction that is something more than a general purpose machine for the invention to be patentable.

The NASSCOM representative stated that Indian IT companies have been aggressively filling patents recently. Their main concern was regarding the machine specific requirements or physical constructional features for granting of patents. The Patent law firms brought forth the point that the practices of the Indian Patent office should be consistent with the practices of the patent office around the globe in line with INDIA’s TRIPS obligations.

Mr.B.P.Singh from the patent office stressed on the legislative intent in excluding software patents by focusing on the report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee that was laid on the table of the Lok Sabha on December 19, 2001. The report stated that:

“In the new proposed clause (k) the words ”per se” have been inserted. This change has been proposed because sometimes the computer programme may include certain other things, ancillary thereto or developed thereon. The intention here is not to reject them for grant of patent if they are inventions. However, the computer programmes as such are not intended to be granted patent. This amendment has been proposed to clarify the purpose.”

Mr.Chaithanya Prasad told the meeting that the patentable subject matter in the case of computer related inventions is thus restricted to those inventions which are “ancillary thereto or developed thereon” to the computer programme. SFLC.IN stressed on the need to use the four part contribution test as explained in the Aerotel/Macrossan case in 2006:

- properly construe the claim

- identify the actual contribution;

- ask whether it falls solely within the excluded subject matter;

- check whether the actual or alleged contribution is actually technical in nature

A few patent agents stressed on the need for algorithms to be patentable if these had a technical effect. However, Mr.B.P Singh was categorical that algorithms and mathematical methods as well as business methods are not patentable. SFLC.IN supported his view by pointing out that the “as such” clause in EPC applies to computer programmes and methods for performing mental acts and business while the per se clause applies only to computer programmes in Indian patent legislation.

These kind of discussions forces one to ponder about the policy making process in India. Why are the non-indian players dominant in such discussions? Why aren’t the domestic stakeholders equally represented? Is this a resource question? Why would any lawyer object to more patents? Why are the questions that have already been decided being re-introduced in such discussions? Is a pro-patent narrative being created for something that is coming owing to the change of business for some of the most powerful owners of government granted monopolies in the world?

Software is algorithms for computers in human readable terms and is therefore not patentable. If mathematics were patentable, there would be less mathematical innovation. Only those who were rich enough to pay royalties, or who benefited from subsidization by government, or who were willing to sign over the value of their ideas to someone richer and more powerful than themselves, would be permitted access to the world of abstract mathematical ideas. Theorems build upon theorems, and so the contributions of those who could not pay rent—and all the further improvements based upon those contributions—would be lost.

SFLC.in hopes that the final guidelines will be in tune with the legislative intent and will prevent the granting of irregular patents in the area of software. The Indian software industry has flourished without patent protection and can continue to do so in the future without fear of litigation from patent thickets by not supporting the grant of software patents. The Indian industry should learn from the position taken by the domestic software industry of New Zealand that worked together for a new legislation to exclude software from patentable subject matter. We believe that computer software expresses abstract ideas, and therefore the ideas themselves will grow best if left most free to be learned and improved by all. The Free Software movement has attracted hundreds of thousands, soon millions of programmers around the world to the making of new and innovative software through the social process that for centuries has been the heart of Western science: “share and share alike.” Indian companies and industry organisations also need to dig deeper within and take a call on whether patent lawyers who benefit from patent litigations and filings, thereby thus have a vested interest should be their face in such consultations.