When the government first rolled out the Sanchar Saathi mobile application, it was framed as a helpful, unified solution for citizens; a single tool to block stolen phones, verify device IMEIs, and report spam or fraudulent telecom activity.

While there are legitimate concerns surrounding fraudulent activity and cybercrimes, an in-depth technical analysis of the application reveals a much more complex and concerning situation, especially when paired with the government’s initial directive for mandatory pre-installation on all new devices.

This blog post provides an engineering-grounded evaluation of the app, dissecting its permissions, architecture, vulnerabilities, and design choices, along with the broader implications for user rights and digital autonomy.

1. Decompilation:

To move beyond assumptions, an independent technical review of the Sanchar Saathi APK was conducted, inspecting:

- The AndroidManifest

- Declared permissions

- Core components (activities, receivers, services, and intents)

These findings were cross-referenced with publicly available analyses (such as the widely circulated OpenTinker report).

Key Finding: The technical baseline is reliable. Permissions, activities, and overall application structure were consistent across independent analyses, allowing for a meaningful assessment of its intended behaviour and permission usage.

2. What is Sanchar Saathi?

At its core, Sanchar Saathi functions primarily as a mobile wrapper for existing web-based functionalities that are already available on government portals. The app itself does not implement complex network logic or telecom-level functions on the device.

The App’s Core Functions are to assist users to:

- Block a stolen device using its IMEI

- Unblock a recovered device

- Check the genuineness of an IMEI

- Report spam or fraudulent calls/SMS

Key Finding: All of these services exist today as simple web forms. None of them inherently requires invasive system-level permissions like reading your entire SMS inbox or your complete call history. Examples of this are the CEIR portal for IMEI blocking/unblocking, IMEI genuineness check websites, and TRAI systems for spam reporting.

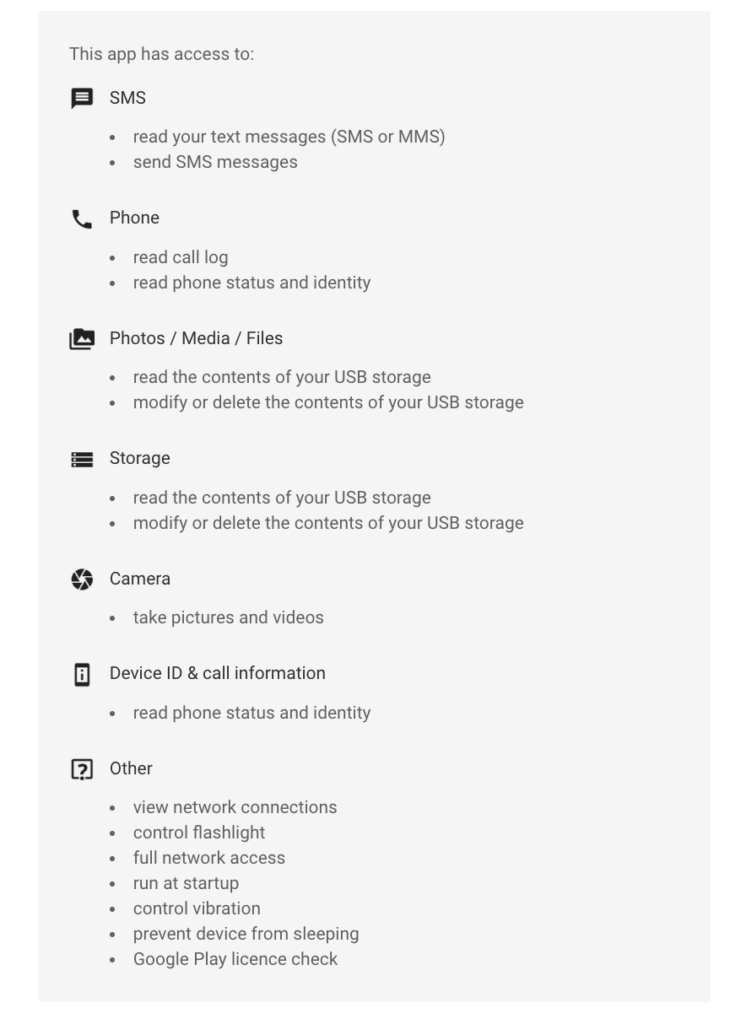

3. Permissions

The app requests broad permissions it does not need for its core operational functionality.

During the initial registration process, the app requests full telephony permissions, including both SMS and call permissions.

Technical Justification provided:

- It sends a verification SMS to the number 14422.

- It attempts to automatically detect the user’s mobile number via telephony APIs.

However, the actual services provided after registration require none of these permissions. The vast mismatch between its functional need and its permission breadth is the core technical concern.

It is unnecessary, avoidable, and significantly expands the app’s security attack surface far beyond what is justifiable.

It also asks for other permissions like – Camera, flashlight, storage, as the user starts using different options available within the application.

This app has access to:

SMS

- read your text messages (SMS or MMS)

- send SMS messages

Phone

- Read the call log

- read phone status and identity

Photos / Media / Files

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Storage

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Camera

- take pictures and videos

Device ID & call information

- read phone status and identity

Other

- View network connections

- control flashlight

- full network access

- run at startup

- control vibration

- prevent the device from sleeping

- Google Play licence check

4. Android’s Permission and Baseline Issues

Android’s model for handling SMS and call permissions is inherently risky because it is an “all or nothing” system.

Once granted, the app is instantly empowered with:

- Full access to all SMS messages (inbox, outbox, stored).

- Complete access to call logs (incoming, outgoing, missed).

- Access to timestamps, call durations, and associated numbers.

- Communication metadata that can be used to map a person’s entire social graph.

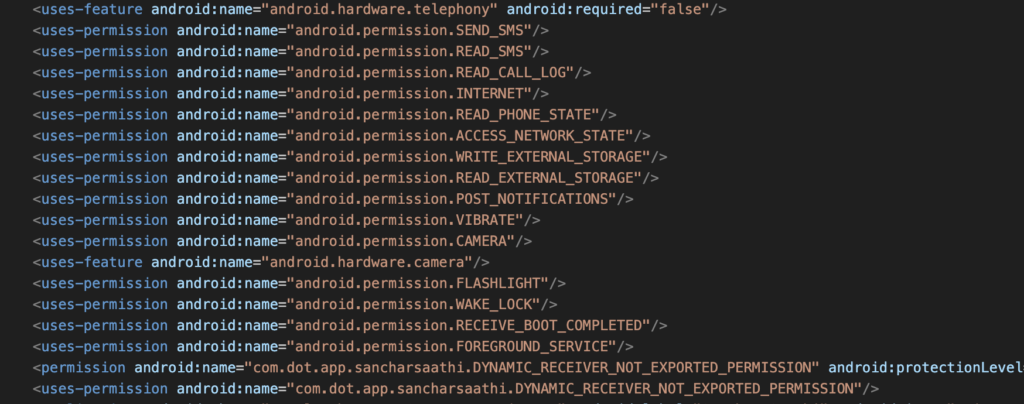

The app requires permissions that grant extensive control and access, as specified in its manifest:

- SMS Access: Uses

android.permission.READ_SMS and android.permission.SEND_SMS. This grants the ability to read all text messages and send SMS without user confirmation, far exceeding the need for a single OTP verification. - Phone and Call Status: Uses

android.permission.READ_CALL_LOG and android.permission.READ_PHONE_STATE. This allows access to the complete call log history and the status of ongoing calls. (Note: Access to non-resettable IDs like IMEI is restricted on modern Android (API 29+)). - Storage Access: Uses

android.permission.READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGEandandroid.permission.WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE. This permits the app to read and modify the shared file system, a broad and unnecessary level of access for a reporting tool. - Camera and Device Control: Uses

android.permission.CAMERAandandroid.permission.FLASHLIGHT. This grants access to the camera hardware (used for IMEI scanning) and control over the flashlight. - Persistent Background Control: Uses

android.permission.RECEIVE_BOOT_COMPLETED,android.permission.WAKE_LOCK, andandroid.permission.VIBRATE. These enable the app to execute tasks persistently after a reboot, keep the CPU awake, and run background activity.

Important Note: Android does not allow granular access, such as limiting the app to only reading OTP messages, restricting access to specific senders, or only viewing communication metadata. If the permission is granted, the app gets access to everything. This is the structural danger.

5. Better and Safer Alternatives

The choice to use invasive permissions for verification is a design choice, not a technical limitation. Android provides several modern, secure mechanisms for application verification that do not require SMS inbox access:

| Safer Alternative | Benefit |

| SMS Retriever API | Allows OTP verification without the READ_SMS permission. |

| SMS User Consent API | Requires the user to explicitly approve reading a single OTP message. |

The Sanchar Saathi app ignores these modern, privacy-preserving APIs and opts for an archaic, unnecessarily invasive mechanism.

6. Forced Pre-Installation

The government’s directive was to compel smartphone manufacturers to:

- Pre-install the app.

- Make it readily visible.

- Ensure its functionalities are not removable or disabled.

This action elevates the application into a quasi-system app, making removal or disabling difficult for the average user. While the app may not auto-enable its permissions, pre-installation fundamentally changes the power dynamic for users. The inherent effect of such a direction is that Users perceive the app as mandatory. Further, Permissions are liable to be granted without careful consideration or full awareness of the risk. Importantly, such a measure also ensures that consent becomes merely procedural, and not meaningful or informed.

When an application carries such high-risk permissions, meaningful, informed consent is an absolute necessity.

7. Vulnerabilities

An app with unnecessary permissions doesn’t just create a privacy concern, but also dramatically expands the attack surface for the entire device ecosystem.

If the app has the power to read all SMS and calls, any vulnerability, either in its network handling, broadcast receivers, deep links, or update mechanism, could be exploited by an attacker to extract sensitive data.

Risk Assessment: More permissions mean more power for an attacker if a breach occurs. Sanchar Saathi creates a single, high-privilege point of failure on millions of devices. Mandatory installation elevates that risk to a national-scale vulnerability.

8. Potential for Surveillance

Even if the app is not currently configured to collect all SMS and call logs, the capability is structurally built into the system in the following ways

- The permissions are granted from Day 1.

- An app update could silently enable wider data collection.

- The central government backend for this data already exists.

The combination of: Broad permissions + State ownership + Centralised backend + Mandatory installation inadvertently creates an architecture with a structural capability for surveillance, regardless of the current stated intent.

Conclusion

The Sanchar Saathi app, in its current form, fails several critical tests:

- Necessity: The app is not technically required; web portals are sufficient.

- Proportionality: Permissions are disproportionately invasive for the limited function.

- Minimal Intrusion: Safer, modern alternatives (like OTP APIs) exist.

- Security Hygiene: Forcing a high-permission app onto millions of devices increases systemic risk.

In technical, privacy, and cybersecurity terms, mandatory installation is unjustifiable.

The application is an example of over-engineering, over-permissioning, and poor design. A responsible, safe implementation should have focused on web-based flows, modern OTP APIs, strict data minimisation, and voluntary installation, avoiding both SMS and call log access entirely.