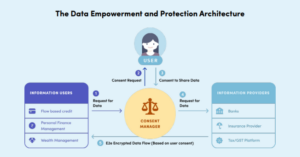

Data evolves over time, and so do its qualities, use cases, commercial potential, and interoperability. If the interoperable nature of data changes, then the models and structures that govern its storage and sharing must follow suit. Datasets that are more portable and interoperable derive a greater utility, due to their non-rivalrous and non-exclusive nature [1], and fully realize the social and economic value of the free flow of data. The execution of the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) is a move in this direction, to explore the potential and opportunity cost of interoperable and portable data.

Launched in 2020, through a public-private effort between iSPIRIT and NITI Aayog [2], the DEPA provides the infrastructure and mechanism for information users to access data from information providers, with the informed consent of the data principals. It promotes the decentralized storage of data and dismantles fragmented, isolated, and inaccessible data silos and monopolies. By rejecting custodian-centric data storage and sharing models, it encourages a user-centric model instead to accommodate changing data access needs. The DEPA aims to avoid the concentration and centralization of data with companies and institutions that control how data structures function. The risks of such patterns are visible due to increasing data leaks, security breaches, and other privacy concerns. By making the process of transferring data more portable and consent-based, it can maximize the data’s economic potential and avoid inaction caused due to data silos. [3]

The DEPA attempts to address these issues through a lens of user empowerment rather than a prevention-of-harm perspective. [4] By providing users with more autonomy and control over the flow of their data, it benefits them by providing access to better services. In the present data-hungry market, not only should companies be benefitting from the existing dynamics and power structures, but also data principals, start-ups, and MSMEs.

The purpose of this data architecture, as defined by NITI Aayog, is:

“By giving people the power to decide how their data can be used, DEPA enables an individual to control the flow of and benefit from the value of her personal data, relying on not only institutional data protection measures but also restoring individual agency over data use” [5]

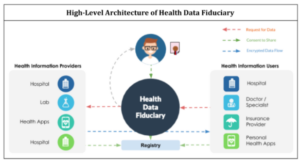

In the context of the digital healthcare system in India, formalized by the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), the lack of technical interoperability remains the most important challenge [6]. Despite the obvious benefits of interoperable health data, interoperability in the healthcare sector has been a slow development, due to a lack of political intent. [7] Control and agency over the flow of data continue to rest with competing institutional interests, rather than individuals. Incorporating the DEPA under the Health Stack would provide a solution to these issues, enhance the value addition of each service availed, and incorporate good data governance practices.

Deployment of Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) under the India Stack

Before we understand this, it’s important to define the parties involved in this exchange:

An Information Provider: any entity that generates or leads to the generation of data pertaining to a data principal;

An Information User: any entity that requires access to this data to provide directed, targeted, and accurate services;

And a Data Principal: an individual to whom the personal data relates.

Usually, if an information user requires any personal data of a data principal, they would directly access this from the information provider, based on the consent of the principal (only in certain circumstances). The consent would be collected by the information provider, who would directly transfer and share this data with the information user. It’s pertinent to note here that the information provider would function as the collector and storer of user data, along with the collector and manager of the user consent. The DEPA overturns conventional bilateral data transfer between an information provider and user by introducing a consent manager.

A Consent Manager is any entity that receives, processes and audits requests for access to personal data. They act as a middle person to grant or deny access to data by information users, based on the consent of the data principal.

Technically functioning as a mediator between data users and data fiduciaries, consent managers take over the responsibility of managing consent from an information provider. They allow users to have a complete overview of the transfer and sharing requests of their data, granting them more power, control, and autonomy. Instead of the conventional consent collection by approaching information providers, the DEPA ensures that users are not circumvented in this process.

This makes the process of granting consent a more audited and supervised process, as under the DEPA consent is not only dependent on the type of data required, but also the information user/data fiduciary that requests it. This ensures that data principals can choose how they want to benefit from data sharing. Consent managers are essentially ‘data-blind by design’ [8] as they have no visibility, control, or even rights to host or store user data. The DEPA also grants data principals the right to allow or deny access to their personal data on a case-to-case basis. This allows for granting informed consent for each data transaction and avoids blanket consent.

Source: NITI Aayog, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (2020)

The first application of the DEPA was in the finance sector, where the Account Aggregator (AA) framework was developed by the Reserve Bank of India. AAs essentially provided a digital platform where a user’s financial data would be consolidated from banks, mutual funds, insurance providers, and tax/GST platforms. [9] Data portability served as a solution where Financial Information Users (FIUs), such as personal finance management, wealth management advisors, etc. could access this data. In an extension to this, it provided for frictionless consented data sharing to determine the creditworthiness of lenders, based on Aadhar’s existing eKYC system, to disburse loans to small entrepreneurs. [10] This was developed on the back of the Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN) which connected lenders to marketplaces and democratized the process of disbursement of loans. It was defined by Nandan Nilekani, its architect, as “a common language between lenders and borrowers”. [11] The DEPA’s expansionary and adaptability powers are one of its greatest strengths as it extended access to other financial management products, such as insurance, savings, etc.

Its success is witnessed by its widespread adoption, which has only been possible through leveraging open and standardized Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), to allow consent managers to compete and integrate their datasets. Essentially, the DEPA restructures the conventional way in which data-intensive companies compete with one another in a free market. It moves the focus from relying on data access, capital, and market dominance to giving companies that ride on efficient and innovative product design, analytics, and value creation a chance. [12]

Implementation of the DEPA into the Health Stack

Under the ABDM, health data is stored in a decentralized manner, with a focus on maintaining privacy and security. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India has designed the ABDM to ensure that individual health data remains secure and is accessible only to authorized entities. The principles, practices, and processes of the DEPA, once adopted in the digital health ecosystem, would be able to achieve this. In practice, under the ABDM, health data is only stored with the healthcare entity that collects it, known as Health Information Providers (HIPs). Access is only granted from them to Health Information Users (HIUs), with the consent of the patient through DEPA. The National Health Authority, MoHFW, or any other state instrumentality, would not have any access, control, or ownership of any of this data, even the data stored in databases of public healthcare providers. [13]

To allow new consent managers to integrate their services into a common sharing system, rather than having to build bilateral relationships with each information provider to access data, the DEPA adopts open APIs. The National Health Authority has extended this to create sandboxes and standardized infrastructure to allow health tech companies to easily incorporate their functions. This architectural design has been developed to further innovation by startups, MSMEs and health-tech entrepreneurs due to ease of linking, compliance, and integration at virtually zero cost.

Source: iSPIRIT, Data Privacy and Empowerment in Healthcare (2018)

Here’s an overview of the data storage approach proposed under the ABDM:

- Decentralized Health Data Storage: The ABDM emphasizes a decentralized architecture for data storage, where health data is stored at multiple levels with the HIPs. This approach towards storage ensures that health data is not consolidated in a single central repository, mitigating the risk of unauthorized access, breaches or leaks.

- Health Information Exchange – Consent Managers (HIE-CMs): The ABDM leverages Health Information Exchanges, which are interoperable platforms for secure data exchange. These HIE-CMs function as the consent managers in the digital healthcare ecosystem and facilitate the sharing of health data among authorized healthcare providers while adhering to strict privacy and security protocols.

- Consent-Based Data Sharing: The Mission includes a consent management framework, allowing individuals to control the sharing of their health data. Individuals can provide consent to specific healthcare providers or organizations for accessing their health information. This consent-based approach ensures that data is shared only with authorized entities and according to the preferences of individuals.

- Secure Data Infrastructure: The ABDM focuses on establishing a robust and secure infrastructure for storing health data. This includes adherence to stringent security standards, encryption protocols, access controls, and regular audits to ensure data protection.

It is important to note that while the central government plays a crucial role in setting the guidelines and framework for data storage and security, the actual storage of health data may involve a combination of public and private infrastructure. The government is collaborating with various stakeholders, including public and private healthcare providers, to assist HIPs with the necessary data storage and exchange infrastructure.

Overall, the ABDM prioritizes decentralized data storage, consent-based sharing, and strict cybersecurity measures to protect personal health data. The aim is to strike a balance between accessibility, privacy, and security while ensuring that authorized healthcare providers can access the necessary information to deliver efficient and effective healthcare services.

In the next part of this two-post series, we will evaluate the unique challenges and risks posed to health data and why the need to obtain consent for processing health data is not just a principle-based approach. Further, we’ll uncover the data storage, transfer, and privacy concerns under India’s health data management policies, the solutions that the DEPA aims to offer in the health stack, and the shortcomings of its application.

Footnotes

[1] Charles I. Jones and Christopher Tonetti, Non-rivalry and the Economics of Data, STANFORD BUS. (Working Paper No. 3716) (Aug. 2019).

[2] India Stack Knowledge Exchange 2022, Press Release, PIB, Ministry of Electronics and IT (Jul. 8th, 2022), https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1840024.

[3] Pouyan Esmaeil Zadeh and Mahed Maddah, The Role of Consumer Consent in Health Information Exchange (HIE), EMERGENT RESEARCH FORUM (2017).

[4] Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture: Draft for Discussion, NITI Aayog (Aug. 2020), https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-09/DEPA-Book.pdf.

[5] Supra Note 4.

[6] JASON, A Robust Health Data Infrastructure, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Apr. 2014), https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/ptp13-700hhs_white.pdf.

[7] Niam Yaraghi, A Sustainable Business Model for Health Information Exchange Platforms: The Solution to Interoperability in Healthcare IT, Centre for Technology and Innovation at Brookings (Jan. 2015), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/HIE.pdf.

[8] Supra Note 4.

[9] Vikas Kathuria, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture: Concept and Assessment, ORF (Aug. 12th, 2021), https://www.orfonline.org/research/data-empowerment-and-protection-architecture-concept-and-assessment/.

[10] Supra Note 3.

[11] Open Credit Enablement Network will democratize credit, help small businesses: Nandan Nilekani, Financial Express (Jul. 22nd, 2020), https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/open-credit-enablement-network-will-democratise-credit-help-small-businesses-nandan-nilekani/2032123/.

[12] Siddharth Tewari, Frank Packer and Rahul Matthan, Data By People, For People, International Monetary Fund (Mar. 2023), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/03/data-by-people-for-people-tiwari-packer-matthan.

[13] Anukriti Chaudhary, Data Privacy and Empowerment in Healthcare, iSPIRIT (Jun. 12th, 2018), https://pn.ispirt.in/depainhealthcare/.