Unlike the US, free speech in India is not absolute. Our Constitution, while guaranteeing the freedom of speech and expression, places “reasonable restrictions” on this basic human right.

Before 2015, online and offline speech were treated on different pedestals under law. As per Section 66A, an infamous provision of India’s Information Technology Act, 2000, anyone who posted material that was grossly offensive, inconvenient, injurious, menacing in character or insulting, could be imprisoned for up to three years.

This draconian provision was struck down by India’s Supreme Court in 2015 for being violative of the constitutionally guaranteed right of free speech and expression, in the landmark case, Shreya Singhal vs Union of India.

Besides championing free speech in the online world, the Supreme Court, in Shreya Singhal, absolved content hosting platforms like search engines and social media websites from constantly monitoring their platforms for illegal content, enhancing existing safe-harbour protection (legal protection given to internet companies for content posted by their users).

The court made it clear that only authorised government agencies and the judiciary could legitimately request internet platforms to take down content. As content hosting platforms are the gatekeepers of digital expression, this was a turning point in India’s online free speech regime.

Despite Shreya Singhal, state authorities continued their use of Section 66A and other legal provisions to curb online speech. In 2017, a youth from the state of Uttar Pradesh was booked under Section 66A for criticising the state’s chief minister on Facebook.

Journalists are often targeted by state authorities for their comments on social media. In September, last year, a Delhi-based journalist was arrested for his tweets on sculptures at the Sun Temple in Konark, Odisha, and another journalist from Manipur was booked under the stringent National Security Act, 1980, and jailed for uploading a video on the internet in which he made remarks deemed to be “derogatory” towards the chief minister of the state.

Proposed amendment

In December, the Union Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, the nodal ministry for regulating matters on information technology and the internet, released a draft amendment to guidelines under the Information Technology Act, which prescribe certain conditions for content hosting platforms to seek protection for third-party content.

The amendment, which was brought along to tackle the menace of “fake news” and reduce the flow of obscene and illegal content on social media, seeks to mandate the use of “automated filters” for content takedowns on internet platforms and requires them to trace the originator of that information on their services (this traceability requirement is believed to be targeted at messaging apps like WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram).

Apart from state authorities, content sharing and social media companies take down content in tandem with their community standards and terms and conditions. This is often arbitrary and inconsistent.

In February, Twitter was heavily criticised for blocking journalist Barkha Dutt’s account after she posted personal details of people who were sending her rape threats and obscene pictures. While blocking her account, Twitter failed to takedown the obscene content directed at Dutt.

Similarly, in March, Facebook blocked the account of prominent YouTuber and social media personality Dhruv Rathee after he shared excerpts from Adolf Hitler’s biography Mein Kampf on his Facebook page.

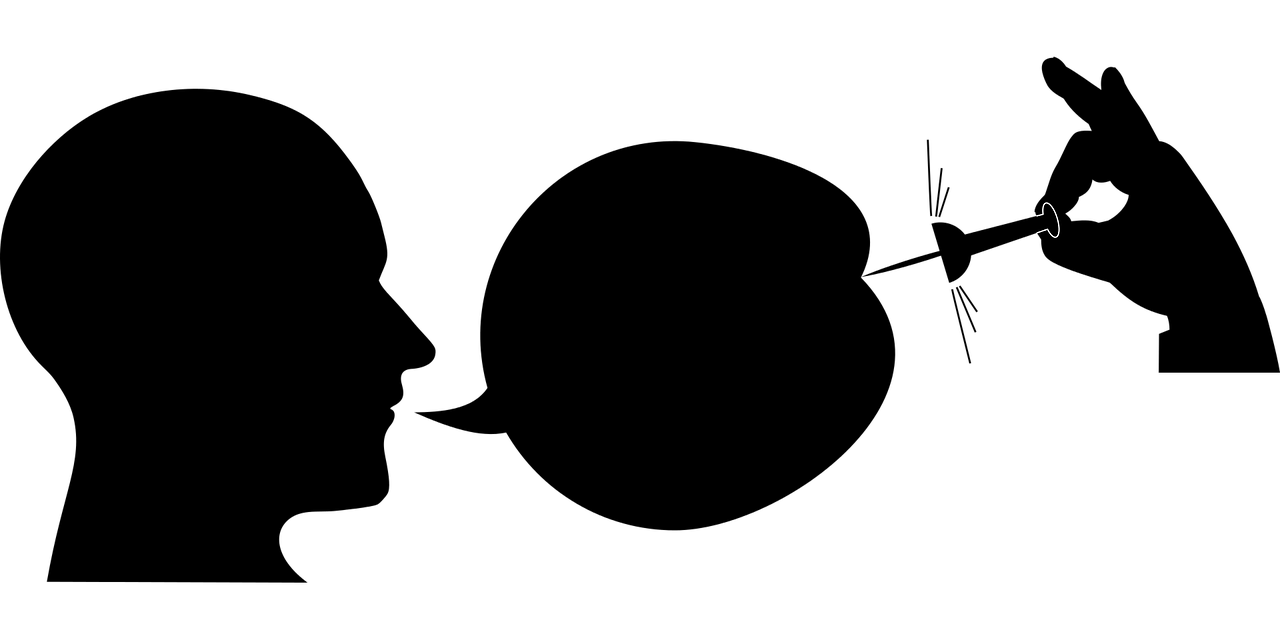

Threat to free speech

Our online speech is heavily dependent on policies (both government and industry lead) which affect digital platforms like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Recognising this fact, SFLC.in, in March, published a comprehensive report which captures the legal landscape in India and key international developments on content liability on internet platforms.

We believe that government regulation such as the draft amendment to the rules that regulate platform liability undermines free speech and privacy rights of Indians in the online world, while promoting private censorship by companies.

Having said that, acknowledging the problems of circulation of illegal content, legitimate access to law enforcement and disinformation on the internet, the law should mandate governance structures and grievance mechanisms on the part of intermediaries, enabling quick takedown of content determined as illegal by the judiciary or appropriate government agencies.

The “filter bubble” effect, where users are shown similar content, results in readers not being exposed to opposing views, due to which they become easy targets of disinformation.

The way forward

Content hosting platforms must maintain 100% transparency on political advertising and law enforcement agencies should explore existing tools under law (such as Section 69 of the Information Technology Act and exploring agreements under the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data or CLOUD Act in the US) for access to information.

Tech-companies must also re-think their internal policies to ensure that self-initiated content takedowns are not arbitrary and users have a right to voice their concerns.

Government agencies should work with internet platforms to educate users in identifying disinformation to check its spread.

Lastly, the government should adhere to constitutionally mandated principles and conduct multi-stakeholder consultations before drafting internet policy to safeguard the varying interests of interested parties.