Do you think it is important to keep your call records private? Do you want the websites you visit and your email contacts to be made public? Should Governments protect the data of its citizens from prying foreign agencies?

Extensive coverage in major publications around the world, particularly The Guardian, as also reported by The Hindu in India has brought under spot light, inter alia, the unprecedented scooping of metadata of telephone and internet communication of citizens around the world including Indians by the National Security Agency of USA. The reports postulate that NSA with its Boundless Informant program, which is a big data analysis and data visualization system, might be collecting or monitoring metadata concerning domestic telecom traffic within India. The newspaper report also quotes Mr. Kapil Sibal, the Telecommunication & Information Technology Minister, who said that the “US government has informed India that the monitoring only involved looking at trends for indications of aberrations”.

In the backdrop of these reports it is important to analyze what constitutes metadata, why is unlawful access to metadata a violation of privacy and an illegal act, and how the Government of India (GoI) has not reacted in a way befitting a sovereign state when the rights of its citizens are violated by a foreign state.

Metadata refers to structured information that describes, explains, locates, or otherwise makes it easier to retrieve, use, or manage an information resource. Metadata is often called data about data or information about information. In simpler terms, it provides information about the communication made. For example, in case of telephone calls, the metadata will reveal the call detail records (CDR): the time and duration of each phone call; the phone numbers of the caller and the recipient; IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) number which is a 15-digit serial number that identifies your wireless phone/device and the location of caller and the recipient at the time of call. The readers may recall a recent controversy involving Mr. Arun Jaitely, the leader of opposition in the Rajya Sabha, whose call detail records were accessed illegally and who asserted how, sometimes, the mere fact that someone called a particular number reveals extremely sensitive information.

In the case of internet communication, the metadata will include IP address, websites accessed, time spent on browsing a website, location, email logs, email recipients, subject lines of emails, mail client used, operating system used amongst other details.

Simply put, by joining the dots as made available by this so called harmless metadata, a lot of facts about a person’s life can be inferred, for example, if repeated calls were made to a sex hotline number by a political leader, nobody needs to know the content of the calls to draw their inferences. As explained by Prof. Edward W. Felten, a computer science and public affairs expert at Princeton University, “Two people in an intimate relationship may regularly call each other, often late in the evening. If those calls become less frequent or end altogether, metadata will tell us that the relationship has likely ended as well and it will tell us when a new relationship gets under-way. More generally, someone you speak to once a year is less likely to be a close friend than someone you talk to once a week. “

He also describes another hypothetical situation: “A young woman calls her gynaecologist; then immediately calls her mother; then a man who, during the past few months, she had repeatedly spoken to on the telephone after 11pm; followed by a call to a family planning center that also offers abortions. A likely storyline emerges that would not be as evident by examining the record of a single telephone call.”

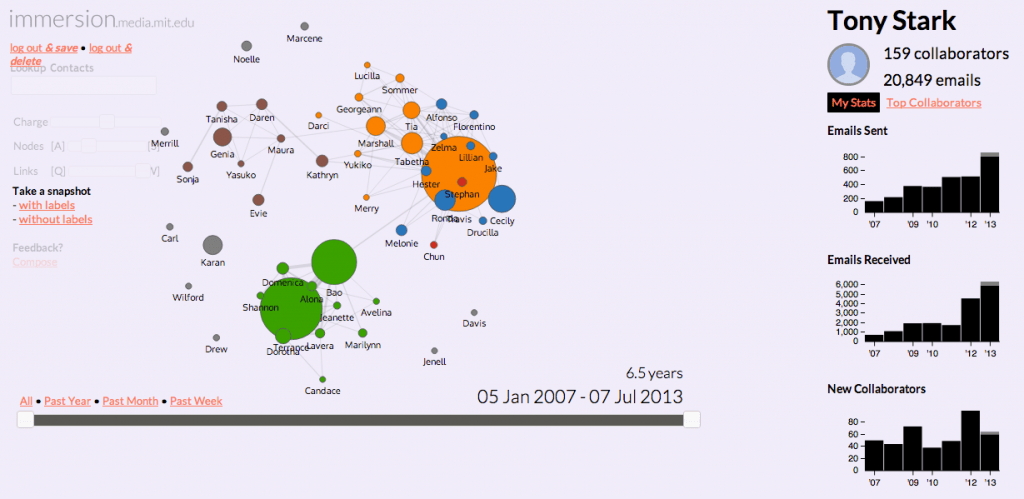

Metadata is machine-readable and this makes it easier to search and collate information. Dedicated protocols could be designed to mine information from the internet and telephone communications. Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Media Lab has created an application called Immersion which turns your email interactions into an interactive infographic. The application helps you to visualize the information that can be gleaned from metadata obtained by accessing your email. Such illustrations underscore the privacy problems associated with metadata mining. In case of an average citizen it can reflect on her relationships; for a professional or a business person it can reflect on her financial transactions; for a journalist it can reveal the identity of her sources.

Snapshot of the immersion tool

In India, the law relating to interception and monitoring of telephone communication is governed by the Indian Telegraph Act, 1887. Information Technology Act, 2000 is the applicable law in the case of internet surveillance. Section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1887 authorises the Government to intercept “messages” for safeguarding public safety or on the occurrence of any public emergency. It states that such authorisation may be permitted on a temporary basis and only when it is “necessary or expedient to do so in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offense”.

In a landmark judgment, PUCL v. U.O.I, the Supreme Court recognised the privacy rights of the citizens in the light of monitoring and surveillance mechanisms. The Apex Court framed guidelines to protect and safeguard the privacy rights of the citizen. Rule 419- A of Indian Telegraph Rules, 1951 was notified based upon the guidelines provided in the PUCL judgment, it provides the procedure and safeguards that must be followed by any law enforcement agency to monitor or intercept messages transmitted by a telegraph. This Rule mandates that a direction of interception of any message can only be issued by an order made by the Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of Home affairs and by Secretary of State to the State Government in-charge of the Home Department. Only in “unavoidable circumstances” can an officer not below the rank of a Joint Secretary duly authorized by the Union Home Secretary issue such an order.

Therefore, the different Agencies under GoI have to statutorily obtain specific authorization from the Competent Authority for each case of lawful interception in accordance with provisions of Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act 1885 and Rule 419(A) of the Indian Telegraph (Amendment) Rules, 2007. There is no general authorisation given to agencies for interception of communication. From time to time, the Central Government lists some agencies which may make such requests for authorisation in specific cases.

The term “message” has been defined under section 3 (3) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1887 as “messages mean any communication sent by telegraph, or given to a telegraph officer to be sent by telegraph or to be delivered”. The Indian Telegraph Act, 1887 does not contain any definition of metadata and does not have any provision protecting access to call detail records. It can be argued that as metadata is transmitted at the time of transmission of a message, such metadata is integral part of a message and should be afforded the same level of protection as a telephone conversation.

The metadata related to internet communication gets greater statutory protection. Section 69 B of the Information Technology Act, 2000 authorises the Government to monitor and collect traffic data or information. The term traffic data as defined under section 69 B, includes any data which could identify any person, computer system or network or location to or form which the communication is or may be transmitted and includes communication origin, destination, routes, time, data, size, duration or type of underlying service and any other information. From the definition it is evident that metadata, as far as internet communication is concerned, is a subset of traffic data. The Information Technology (Procedure and safeguard for monitoring and collecting Traffic data or information) Rules, 2009 framed under Sub-section 3 of Section 69 B, provides for the safeguards and procedure that needs to be followed by the law enforcement agencies in cases of monitoring traffic data. As monitoring or collecting traffic data affects privacy of individuals the procedure and safeguards for interception of traffic data is similar to the procedure for tapping telephone calls.

Thus, the Information Technology Act, 2000 and Indian Telegraph Act, 1887 provide that monitoring or surveillance over any communication channel conducted without authorisation of the Government will be considered unlawful. In this backdrop, the acts of monitoring metadata records of Indian citizens by an intelligence agency of a foreign country is clearly an illegal act or did the U.S. Intelligence agencies obtain specific authorization from the Competent Authority i.e. a Secretary in the Ministry of Home Affairs before collecting metadata about Indians? Has NSA like the NTRO been added to a list of agencies authorised by the GoI to intercept and monitor telephonic data of Indian citizens? Is there any oversight of these activities? Are the administrative safeguards built in via subordinate legislation serving their intended purpose and protecting the privacy rights of the citizens as was mandated by the Supreme Court in the PUCL judgment? Can these acts be brushed aside as mere monitoring of trends or aberrations? And if yes, what kind of trends and aberrations are being monitored? The American agencies have justified their extensive, unprecedented spying to their own citizens by insisting that their intelligence collection activities are focused on acquiring foreign intelligence and counterintelligence in accordance with US laws but why did GoI permit such large scale spying of its citizens?

The metadata monitoring could also reveal a lot of information about the communications of Indian political leaders and government officials. Recent revelations about targeting of Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel’s cellphone by the U.S. Intelligence agencies enunciate this possibility. Has GoI explored this possibility with respect to its own officials?

It is long past the time for the Legislature to update our archaic laws to ensure that before anyone randomly digs and wades through our lives, they demonstrate to a judicial authority, probable causes worth impinging our privacy rights. However, if our elected representatives decide to hand over the rights of their citizens to foreign spy agencies, which branch of the government will come to our rescue?